Eye For Film >> Movies >> Inhale (2024) Film Review

Inhale

Reviewed by: Mariam Razmadze

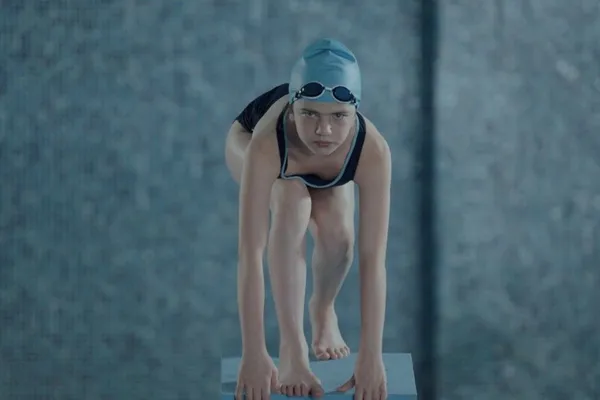

Myths have long haunted the perceptions of female athletes’ performance during their menstrual cycle. The characters of Melana Sokahdze’s 2024 debut short Inhale, which premiered at the Kutaisi International Short Film Festival, are no exception. Similarly to the majority of the Georgia, where the film takes place, they treat the natural occurrence to such a sacred degree, they never name it, and simply say ‘it happened’ when the protagonist Nino (Barbare Topadze), experiences it for the first time right before her big swimming competition.

This is not a classic sports film that relies on an adrenaline rush to keep viewers on edge; it merely uses the swimming competition as a practical backdrop for a personal yet universal story. The match is particularly important for Nino because her father, a successful former swimmer, is in the stands to support her. The title could apply not only to what the girl must do before her match to deliver a top-tier performance, but also to the baffling situation she finds herself in, which she can only exhale from once she endures it.

Amid various degrees of shock, concern and even intimidation, the film examines a climate of emotional distance, in line with a tradition of minimising women’s experiences in Georgian society. This is well established in scenes in which Nino and a friend react with confusion to the girl getting her period. They try to hide it from their trainer, who ultimately finds out and is shown discussing the challenges of coaching female athletes with a colleague – it’s a way of addressing the issue without bordering on cliché.

A key merit is the accurate portrayal of young girls’ shame over womanhood in a male-centered society, never more apparent than when Nino begs her friend not to tell the coach about the incident. Also notable is Topadze’s central performance, which carries the film, although she is never given enough space for the kind of dramatic acting she is clearly gifted at.

The aquatic setting is suitably dominated by the blue tones of the cinematography, with the only exception being the unidentified streaks of red that appear in the pool – it is left to the viewer to guess whether the blood is real or the fruit of Nino’s fearful imagination. Despite the dynamic nature of the sport, Sokahdze’s camera tends to remain still, focusing on human emotion rather than action. Disengaged from notions and movement and energy, the camerawork implies the choice of sport was merely a particular convenience to get the film’s primary message out there.

Ultimately, the script betrays its premise by disregarding Nino’s primary challenge – the skepticism from her male coach towards her ability to perform in her condition – and simply jumps to a rushed conclusion with no real build-up nor resolution. There is a certain aura of overly feminist advertisement that capitalises on the issue of women in sports; the moment when the protagonist tells the coach she knows what she is doing, and gets in the water despite being told not to, feels too convenient of a screenwriting choice. However, it will warm the hearts of those who believe that any narrative counts if it breaks the silence over stigmatised topics.

Reviewed on: 06 Oct 2025